Governor-General David Hurley announced on 12 August 2020 that Queen Elizabeth II has approved the posthumous awarding of the Victoria Cross to WWII hero Edward 'Teddy' Sheean.

The 18-year-old had less than two years at sea and was serving on the minesweeper HMAS Armidale when it came under heavy attack from Japanese aircraft off the coast of what is now Timor-Leste in 1942.

Sheean is recorded as helping launch life rafts before returning to fire at enemy aircraft, despite the order having been given to abandon ship.

The Governor-General said he had relayed the news to Sheean's nephews on Wednesday, describing it as a momentous occasion for the family.

"In my conversations with them, their pride and emotion was very evident," he said.

What a wonderful way to highlight the service and sacrifice of a young sailor serving his county. Let us look back on the the story of Teddy Sheean and the HMAS Armidale.

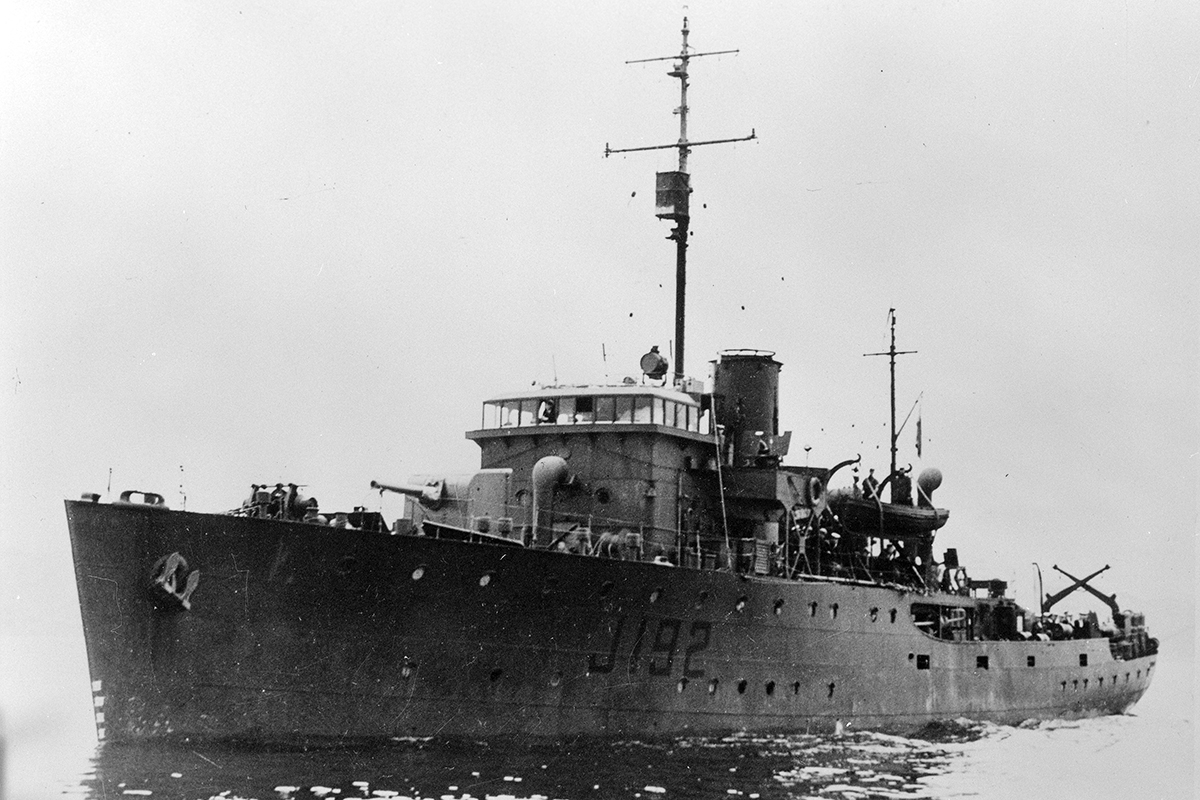

HMAS Armidale (I) was one of sixty Australian Minesweepers (commonly known as corvettes) built during World War II in Australian shipyards as part of the Commonwealth Government’s wartime shipbuilding programme. Twenty were built on Admiralty order but manned and commissioned by the Royal Australian Navy. Thirty six (including Armidale (I)) were built for the Royal Australian Navy and four for the Royal Indian Navy.

Following a workup period Armidale (I) was brought into operational service as an escort vessel protecting convoys operating between Australia and New Guinea. That service ended in October 1942 when she was ordered to join the 24th Minesweeping Flotilla at Darwin. Armidale arrived at Darwin on 7 November 1942.

Edward Sheean (1923-1942), sailor, was born on 28 December 1923 at Lower Barrington, Tasmania, fourteenth child of James Sheean, labourer, and his wife Mary Jane, née Broomhall, both Tasmanian born. Soon afterwards the family moved to Latrobe. Teddy was educated at the local Catholic school. Five ft 8½ ins (174 cm) tall and well built, he took casual work on farms between Latrobe and Merseylea. In Hobart on 21 April 1941 he enlisted in the Royal Australian Naval Reserve as an ordinary seaman, following in the steps of five of his brothers who had joined the armed forces (four of them were in the army and one in the navy). On completing his initial training, he was sent to Flinders Naval Depot, Westernport, Victoria, in February 1942 for further instruction.

In May Sheean was posted to Sydney where he was billeted at Garden Island in the requisitioned ferry Kuttabul, prior to joining his first ship as an Oerlikon anti-aircraft gun-loader. Granted home leave, he was not on board Kuttabul when Japanese midget submarines raided the harbour and sank her on 31 May. See: Japanese Attack Sydney Harbour

Eleven days later he returned to Sydney to help commission the new corvette H.M.A.S. Armidale, which carried out escort duties along the eastern Australian coast and in New Guinea waters. Ordered to sail for Darwin in October, Armidale with Sheean, arrived there early next month.

On 24 November 1942 Allied Land Forces Headquarters approved the relief/reinforcement of the Australian 2/2nd Independent Company which at that time was holding out in Japanese occupied Timor.

The withdrawal of 150 Portuguese civilians was also approved and consequently plans were made in Darwin for the Castlemaine, Armidale and Kuru (Lieutenant JA Grant, RANR), a shallow draught, 76 foot wooden motor vessel, to effect the relief operation which was code named Operation HAMBURGER.

The proposal was for the three ships to each make two separate runs into Betano on Timor's southern coastline. The first run was planned for the night of 30 November-1 December. HMAS Kuru sailed from Darwin at 22:30 on 28 November preceding the two corvettes. She was delayed en route due to adverse weather conditions and consequently did not reach Betano until 23:45 on 30 November.

Both the corvettes came under aerial attack from a single aircraft, having been spotted leaving Darwin by Japanese reconnaissance aircraft. Although they suffered no damage, there was concern that their mission had been compromised. However, they were ordered to proceed and Bristol Beaufighters were sent to provide aerial cover. The ships came under attack twice more, each time by formations of five bombers which dropped some 45 bombs, and also machine gunned from a low level. The Beaufighters drove off the enemy aircraft and, despite minor damage, the ships reached Betano at 3.30 am on 1 December but no-one was waiting. They left without landing the troops.

Kuru in the meantime had embarked 77 Portuguese women and children at Betano and was sailing south when she met up with Castlemaine. Just as the transfer of the Portuguese from Kuru to Castlemaine was completed, enemy bombers appeared again, forcing the ships to seek cover in a nearby heavy rain squall.

Armidale and Kuru were then ordered by the Naval Officer-in-Charge in Darwin, CDRE C J Pope, to return to Betano to complete the troop operation. Castlemaine headed back to Darwin, at the same time searching for two downed airmen from a Beaufighter.

Armidale and Kuru soon came under fierce aerial attack and became separated in the chaos. For almost seven hours Kuru was attacked by some 44 fighters, suffering damage to the engine when shrapnel penetrated the hull. Initially instructed by Darwin to complete the operation, Kuru was then ordered to return to Darwin after Japanese cruisers were reported to be in the area.

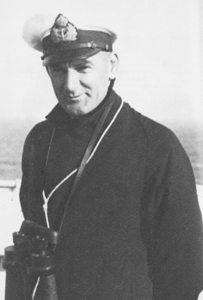

At about 1.00 pm HMAS Armidale was attacked by five Japanese bombers. Requesting air cover from Darwin, LCDR Richards was told fighters would be there at 3.45 pm. CDRE Pope famously signaled that ‘air attack is to be accepted as ordinary, routine, secondary warfare’. This type of warfare was undertaken exceptionally well by the Japanese air crews and Pope was later criticized for his apparent dismissal of aerial attack as being a significant element of warfare.

At 3.00 pm nine Japanese bombers, three Zero fighters and a float plane began attacking the single corvette. The fighters strafed the ship from low levels while the bombers attacked from different directions loosing their torpedoes at the gallant ship.

I had watched our gunner, Lou Lyndon, fire at the Zeros as they flew in low to machine-gun the ship. He seemed to be spot on, the tracers seemed to penetrate the planes’ windscreens and sides as they flashed over us, but the Japs didn’t hesitate. They just kept coming. Ordinary Seaman Rex Pullen

Maneuvering desperately in an attempt to avoid the torpedoes, Armidale was struck by two and heeled sharply to port.

Most of the soldiers crowded into the mess deck were killed in that first blast. [They] would have felt this black, hopeless anguish before the sea rushed in. Ordinary Seaman Col Madigan

The order to abandon ship was given; rafts were cut loose and a motor boat freed before the men took to the water and Armidale sank. Leading Seaman Leigh Bool recalled:

Ratings were trying to get out lifesaving appliances as Jap planes roared just above us, blazing away with cannon and machine guns. Seven or eight of us were on the quarterdeck when we saw another bomber coming from the starboard quarter. It hit us with another torpedo and we were thrown in a heap among the depth charges and racks. We could feel Armidale going beneath us, so we dived over the side and swam about 50 yards astern as fast as we could. Then we stopped swimming and looked back at our old ship. She was sliding under, the stern high in the air, the propellers still turning.

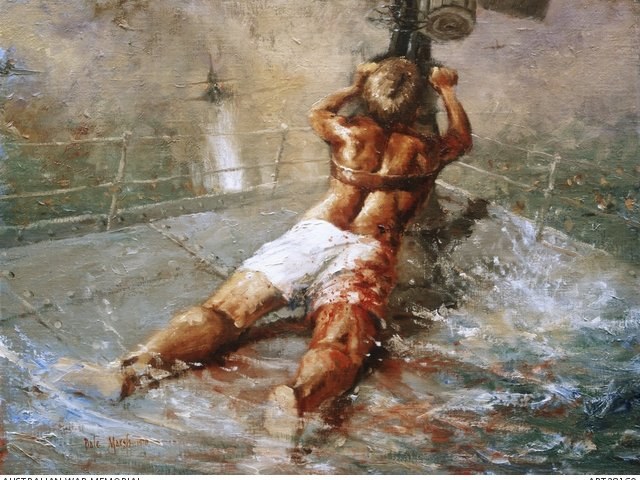

Once Teddy Sheean had helped to free a life-raft, he scrambled back to his gun on the sinking ship. Although wounded in the chest and back, the 18-year-old sailor shot down one bomber and kept other aircraft away from his comrades in the water. He was seen still firing his gun as Armidale slipped below the waves. Only forty-nine of the 149 souls who had been on board survived the sinking and the ensuing days in life-rafts.

Now a 102 sailors and soldiers were now without a ship and their ordeal had just begun. Japanese airmen machine gunned the oil-soaked survivors before leaving the area – their work done. In the water, the survivors found themselves in dire straits. The motor boat, the damaged and submerged whaler and a Carley float were gathered up; fuel drums, painters’ planks and other flotsam were lashed together as a makeshift raft. The men clambered aboard as best they could although not all could fit. Sea snakes swam amongst them and sharks fed on the dead. In an effort to deter the sharks, the men would yell and scream and thrash the water when one came too close.

Right through that first night we heard the noise of water being disturbed. It was either sharks eating some of the bodies or blokes giving up and drowning. We did not know and it was better not to know. Telegraphist Denis Reedman

The sun was hellish by day but after sundown and during the night the air was freezing. No wonder we found a few missing at sunrise roll call. Ordinary Seaman Rex Pullen.

When no rescue ship arrived, the Captain LCDR Richards made the decision to take 16 of the most badly injured of the ship’s company plus some fit rowers in the motor boat and head south for the Australian reconnaissance area; Timor was closer but certainly not safer. He had only a pocket compass and the stars to guide him. They were eventually sighted by an RAAF Hudson on 6 December and rescued by HMAS Kalgoorlie, another Australian corvette. Two of the men aboard the motor boat died before rescue arrived.

After some trouble with the Javanese soldiers, they and their Dutch officers were given the Carley float; they floated away and were never seen again. The 8.8 m (29-foot) whaler was in bad condition and in a feat of exceptional ingenuity it was docked with the raft and the holes patched and plugged with canvas, rag and even clothing. The whaler held 26 RAN and three AIF personnel and on 5 December under the command of LEUT Lloyd Palmer it left the half-submerged makeshift raft and the men began rowing to Australia – 470 kilometers away. Ordinary Seaman Rex Pullen recalled:

Day 6 for the whaler crew was, if anything, worse than Day 5. Of course, we were quickly using up our energy and our sores were getting worse. Even to hold the oar was an effort with our cracked, swollen and festering hands. How long could we last?

On 7 December the raft was sighted by a searching Catalina aircraft. On 8 December both the raft and the whaler were seen by a Catalina but the sea was too rough to land. Aboard the whaler, food and water ran out; the men drank urine and tried to catch fish and gulls with their bare hands.

Ordinary Seaman Col Madigan recalled:

A tin of bully beef divided up into half-inch cubes and handed out … Then a sip of water, or condensed milk – then nothing. The belly shrunk, no evacuation, no water – could he drink his urine? Put it in that condensed milk can and woof [sic] it down; it was still warm, it made him retch. O

No food or water to speak of was quite evident. I was looking into faces covered in despair – and oil – and the eyes were sinking back into their sockets. Ordinary Seaman Rex Pullen

Ulcers and severe sunburn plagued them and they suffered delusions and were disoriented. On 9 December parcels of food and water were dropped by Hudson bombers as they waited for rescue. Some three hours later HMAS Kalgoorlie appeared and put its scrambling nets over the side for the Armidale men. Eight days after the sinking they were a pitiful sight but had achieved an epic feat of survival under appalling conditions.

Our legs were like strips of liquorice and we had to be carried in to the mess deck where lovely hot soup or stew was being issued to survivors – for surely that’s what we were now! After a feed or as much food as we could manage, each one of us was carried to the showers where we sat or knelt on the deck while Kalgoorlie sailors helped us clean ourselves up. Boy, oh boy! – soap and hot water! What a combination! What a luxury! Ordinary Seaman Rex Pullen

They were a pitiful sight. Their condition was appalling, with sunburnt, blistered, ulcerated skin covered in caked fuel, oil and salt. Fred Still, HMAS Kalgoorlie

Twenty-eight survived the whaler voyage and as the Kalgoorlie crew lifted the whaler aboard it broke apart – they had been rescued just in time, having somehow rowed just over 200 kms, almost halfway to Darwin.

But the men in the raft were never seen again despite days of searching. The raft was in poor condition so it may have broken up although no wreckage was sighted.

It wasn’t really a raft, it was something made up, objects off Armidale’s deck. Rope, oil drums, French mine-sweeping floats, Denton floats, the small Carley raft and painting planks; these were all collected at dawn, after the first lonely night. Ordinary Seaman Col Madigan

There was hope that they had been taken as POWs but no record of them was ever found. The third explanation was that they were picked up by a Japanese warship and executed.

Sheean was mentioned in dispatches for his bravery. A Collins-class submarine, launched in 1999, was named after him—the only ship in the R.A.N. to bear the name of an ordinary seaman.

In 2013, as part of an inquiry into unresolved recognition for past acts of naval and military gallantry and valour it was noted that arguments put forward in submissions against the award included "if it is decided that the VC was denied because the administrative arrangements prevailing at the time were inappropriate and that current conditions should apply, then it is incumbent on the awards system to reassess all past award through a modern prism".

Another argument made, according to the 2013 review, was "without wanting in any way to detract from the very real gallantry displayed by Ordinary Seaman Sheean … the majority of claims made about Sheean's actions post the date of his death are inaccurate at best and in many cases preposterous".

A Defence Honours and Awards Tribunal in Hobart last year re-examined the 2013 findings, with Defence Minister Linda Reynolds announcing last Wednesday the review "did not present any new evidence that might support reconsideration of the valour inquiries recommendation".

Ray Leonard, who was aboard the Armidale, told the inquiry the Naval Officer in Charge in Darwin, Commodore Cuthbert Pope and "other senior naval officers met them with formality, distance, coldness and even an implied threat".

"Dr Leonard recalled that Pope said that 'none of you must say a word about the sinking of Armidale to anyone'," the inquiry recorded.

"Dr Leonard said he was left with the impression that Pope thought the survivors had failed in losing their ship, and he felt that this was a factor in [Armidale's Commanding Officer] Richards not getting another command."

Ray Leonard said after being admitted to hospital for a few days, the surviving members of the ship's company were sent their separate ways, "some overland in trucks, others returning to eastern Australia via sea with no opportunity to talk, because they were forbidden from doing so".

Edward Sheean remains the recipient of a Mentioned in Dispatches (MiD), an Imperial form of recognition of bravery citing his name in an official report.

In 1999, a Collins Class submarine was named after him — only one of two Navy vessels to bear the name of a sailor. Teddy Sheean has now been posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.