Japanese Attack Sydney Harbour

Sydney Harbour Circa 1942

In May and June 1942 the war was brought home to Australians on the east coast when the Japanese attacked Sydney Harbour from the sea.

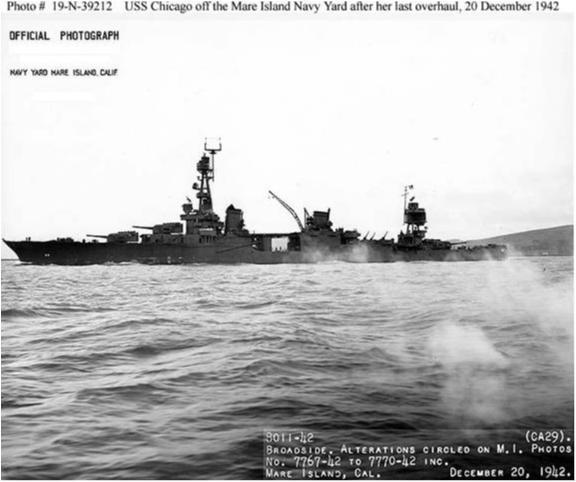

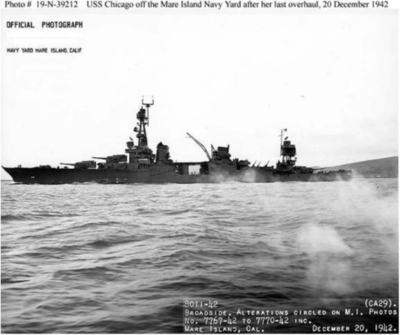

In the late afternoon of 31 May 1942 three Japanese submarines, I-22, I-24 and I-27, sitting about seven nautical miles (13 kilometres) out from Sydney Harbour , each launched a Type A midget submarine for an attack on shipping in Sydney Harbour . The night before, I-24 had launched a small floatplane that flew over the harbour, its crew spotting a prize target - an American heavy cruiser, the USS Chicago . The Japanese hoped to sink this warship and perhaps others anchored in the harbour.

Japanese Midget submarine which took part in the unsuccessful attack in Sydney Harbour, 31 May 1942

EIGHTY FEET LONG, IT IS DIVIDED INTO THREE SECTIONS, DOOR OPENINGS BEING APPROXIMATELY 13" WIDE AND 30" HIGH. ONLY SOURCE OF POWER IS BY MEANS OF BATTERIES OF WHICH SUBMARINE HAVE 208. THE SPEED OF THE VESSEL FOR A SHORT BURST WOULD BE PROBABLY 20 KNOTS, CRUISING SPEED 8 KNOTS.

USS Chicago off the Mare Island Navy Yard after her last overhaul, 20 December 1942

HMAS Kuttabul

After launching the three two-man midget submarines, the three mother submarines moved to a new position off Port Hacking to await the return of the six submariners sent into the harbour. They would wait there until 3 June.

All three midget submarines made it into the harbour. Electronic detection equipment picked up the signature of the first (from I-24) late that evening but it was thought to be either a ferry or another vessel on the surface passing by. Later, a Maritime Services Board watchman spotted an object caught in an anti-submarine net. After investigation, naval patrol boats reported it was a submarine and the general alarm was raised just before 10.30 pm . Soon afterwards, the midget submarine's crew, Lieutenant Kenshi Chuma and Petty Officer Takeshi Ohmori, realising they were trapped, blew up their craft and themselves.

Before midnight , alert sailors on the deck of USS Chicago spotted another midget submarine. They turned a searchlight on it and opened fire but it escaped. Later, gunners on the corvette HMAS Geelong also fired on a suspicious object believed to be the submarine.

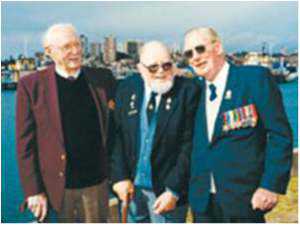

The response to the attack was marred by confusion. Vision was limited and ferries continued to run as the midget submarines were hunted. At about 12.30 am there was an explosion on the naval depot ship HMAS Kuttabul , a converted harbour ferry, which was moored at Garden Island as an accommodation vessel. The crew of the midget submarine from I-24 had fired at the USS Chicago but missed, the torpedo striking the Kuttabul instead. Nineteen Australian and two British sailors on the Kuttabul died, the only Allied deaths resulting from the attack, and survivors were pulled from the sinking vessel.

The three survivors from the HMAS Kuttabul next to the former berth of the Kuttabul on June 1. From left is Neil Roberts, Colin Whitfield (RNZN) and Bill Williams.

Japanese Midget submarine No. 21 being raised by the bows from the harbour by a floating crane during a salvage operation

A second torpedo fired by the same midget submarine ran aground on rocks on the eastern side of Garden Island , failing to explode. Having fired both their torpedoes, the crew made for the harbour entrance but they disappeared, their midget submarine perhaps running out of fuel before reaching the submarines' rendezvous point.

The third midget submarine from I-22 failed to make it far into the harbour. Spotted in Taylors Bay and attacked with depth charges by naval harbour patrol vessels, Lieutenant Keiu Matsuo and Petty Officer Masao Tsuzuku, shot themselves.

The mother submarines departed the area after it became obvious that their midget submarines would not be returning. The submarine I-24 is believed to have been responsible for a number of attacks on merchant ships as well as shelling Sydney Harbour a week later.

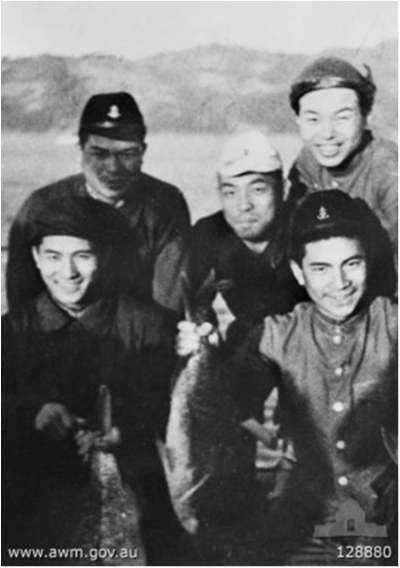

Group portrait of Midget Submarine trainees in training in Kure , Japan

Identified front left is Lieutenant (Lt) Keiu Matsuo; and rear left is Lieutenant Kinshi Chuma both commanders of Midget Submarines launched from carrier submarines I-22 and I-27, in the attack on SydneyHarbour on 31 May 1942 . Lt Chuma's submarine was caught in the boom net and blown up by its crew of two. Both of the officers were among the four bodies subsequently recovered.

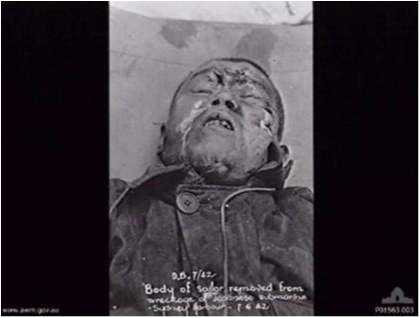

The bodies of the four Japanese crewmen from the midget submarines launched by I-22 and I-27 were recovered when these two midget submarines were raised. They were cremated at Sydney 's Eastern Suburbs Crematorium with full naval honours. Rear Admiral Muirhead-Gould, in charge of Sydney Harbour defences, along with the Swiss Consul-General and members of the press, attended the service. The admiral's decision to accord the enemy a military funeral was criticised by many Australians but he defended his decision to honour the submariners' bravery. He also hoped that showing respect for the dead men might help to improve the conditions of the many Australians in Japanese prisoner of war camps.

THE UPPER BODY OF A DEAD JAPANESE SUBMARINER REMOVED FROM THE WRECKAGE OF MIDGET SUBMARINE 21 (M22), RECOVERED FROM SYDNEY HARBOUR

1943. Canberra , ACT. WRANS from HMAS Harman Naval Wireless Station pose beside a Japanese midget submarine on display outside the Australian War Memorial.

In 1968, Lt Matsuo's mother traveled to Australia to visit the spot where her son had died. During her visit she scattered cherry blossoms in the water where her son's midget submarine had been located and later she presented a number of gifts to the Australian War Memorial.

Prime Minister John Curtin allowed the Japanese Ambassador, Tatsuo Kawai, to take the ashes of the 4 submariners back to Japan after their cremation. Tatsuo Kawai arrived at Yokohama pier in October 1942 aboard the Kamakura Maru with the ashes of the four sailors in four white boxes. These four boxes had been placed on a large altar in front of a flag of the Rising Sun on board the Kamakura Maru during the journey to Japan .

On Sunday 12 November 2006 at about 9am , seven scuba divers met at Long Reef Beach north of Sydney for another fun day of scuba diving. They decided to head for a spot they had marked four months earlier. Their fish finder had noted something interesting on the sea floor. The seas had been too rough that earlier day to investigate, so they had decided to leave it to a calmer day. So on the morning of the 12 November 2006 , they used their GPS to revisit the spot as that day was very calm.

The object was in 70 metres of water, so after doing all their calculations they determined that they could only stay at the sea floor for about 12 minutes. They would require two decompression stops on the way back to the surface. The went down to the bottom and saw a large object covered in fishing net. They maneuvered to one end of the object and saw propellers sticking out of the sand. They started to realise what the object was. Paul Baggott swam back to the middle of the object and saw what looked like a conning tower. With much excitement, he then moved towards what he now believed to be the front of a submarine, to confirm his assumption by looking for torpedo tubes. His assumption was confirmed!!

The approximate location of the M24 is several kilometres off the coast and somewhere between Long Reef and Barrenjoey Headland. The Google Earth link below is only a rough indication of the general area.

The divers all met with the Director of the Naval Heritage Collection, Commander Shane Moore who has since confirmed that they had indeed located the missing M24 Japanese Midget Submarine. Commander Moore shared his knowledge of M24 and its submariners with the divers. He told them that Japanese tourists have often arrived at Garden Island to lay a wreath at the Conning Tower memorial near Woolloomooloo in Sydney .

60 Minutes produced a segment on the diver's discovery which went to air on 26 November 2006 .

The divers all share a concern for the ongoing conservation of the wreck of the submarine. They are keeping the exact location a secret to avoid scavengers desecrating the wreck. It is likely that it still contains the remains of the two Japanese sailors:-

Lieutenant Katsuhisa Ban

Ensign Mamoru Ashibe

Ban and Ashibe were not initially selected for the attack on Sydney Harbour . They were on the standby list. Following an accidental explosion on the mother submarine I-24 about two weeks before the attack, they were placed on the mission.

Discussion between the Australian and Japanese governments will no doubt continue for some time before a decision is made on the fate of the wreckage of Japanese midget submarine M24.

Mr Mark Edwell holds his latest museum piece a WW2 Japanese Gyroscope believed to be from one of the Japanese Midget Submarines that attacked Sydney Harbour on 31 May 1942 .

In early June of 2007 my friend and fellow historian Mr Mark Edwell bought a Japanese WW2 Gyroscope. This Gyroscope came from a Merchant Seaman who told the story of how it was recovered from one of the Midget Submarines that came into Sydney Harbour during WW2, the Gyroscope sat in a private house on the central coast of NSW for the last 35 years.

The Australian War Memorial made several attempts to purchase this item and they confirmed that it is indeed the Gyroscope from a torpedo of a Japanese Midget Submarine. While it is only a story and can not be confirmed, the Merchant Seaman stated to the previous owner that it was in fact recovered from the M24 and they were responsible for the sinking of the craft.

The only evidence that supports this theory is that the Gyroscope is contained within a wooden box that has no signs of water damage that you would expect if it had been taken from the raised midget submarines from Sydney Harbour .

Japanese 140-millimetre naval shell, one of ten fired by a Japanese submarine on 8 June 1942

This shell failed to detonate and was recovered from Manion Avenue, next to the Woollahra Golf Links. It had damaged the top story of the Grantham Flats, occupied by Ernest Hirsch and his family. The shell smashed through his mother's bedroom, passed across her floor and through another two internal walls before stopping on the stairs. Hirsch and his family had fled the impending violence in Nazi Germany five years earlier, deciding to settle in "peaceful" Sydney .

Air raid warden Harry Woodward bravely carried the shell to the golf links, where it was defused by a navy demolition team.

On the 8 th June 1942, the Japanese submarine I-24 was cruising at periscope depth 9 miles south west of the Macquarie light near Sydney. Just after Midnight she surfaced and pointed her deck gun towards Sydney. The Commander (Hanabusa) gave a target indication to his gunnery officer (Yusaburo Morita). The orders were to take aim directly at the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Moving north west towards the coast, Yusaburo fired a volley from his deck gun. Ten shells were fired within 4 minutes. All of which came rained down on the suburbs of Woollahra, Rose Bay and Bellevue Hill.

Ernest Hirsch poses near shell damage on his home

By the time I-24 had finished firing, the searchlights on the shore had been turned on. The coastal batteries were ready to fire around 10 seconds after the Japanese fired their last shell.

Only one of the Japanese shells actually exploded. The Japanese probably used armour-piercing rounds designed to punch through steel plated ships, although they had similar instances with other shells not detonating.

One of the I-24's Salvos hit and penetrated a double brick wall of Grantham Flats, located on the corner of Manion Avenue and Iluka Streets in Rose Bay . A resident (Mr Ernest Hirsch) and his family lived in Grantham Flats. Ernest Hirsch was awoken by the shell came crashing across the floor of his mother's room and passed through another two internal walls, finally coming to rest on the stairs. Lucky enough for the residents the shell had failed to explode. Ernest's mother ended up covered in debris. Escaping unharmed with Ernest suffering a fractured foot when he was buried under a pile of broken masonry. Ernest's wife and 18 month old son were in another room and were not injured.

Home damaged in Sydney 's eastern suburbs by shelling from Japanese submarine

The unexploded shell was carried by Harry Woodward and two others to a nearby park where they temporarily buried it. The Navy demolition team recovered it later for detonation.

Other shell's landed in Bradley Avenue , Bellevue Hill and destroyed the back rooms of Mrs. M. McEachern house. It also damaged the house next door. Once again the shell did not explode. Mrs. McEachern was in bed at the time but not asleep. She heard a shell whistle by and then a thud. She heard two more shells whistle. The third and final shell was the one that hit her house.

Another shell hit the gutter outside a small two storey grocery store run by Mr & Mrs. S. J. & Alice Richards on the corner of Small and Fletcher Streets, Woolahra. It shattered all the windows in the building. Alice and her 2 children hid under the bed. When they eventually came down stairs they found their shop was wrecked.

Other shells fell at: 9 Bunyula Road Bellevue Hill , 68 Streatfield Road Bellevue Hill

67 Balfour Road Rose Bay , 1 Simpson Street Bondi , Olola Avenue Vaucluse

Yallambee Flats, 33 Plumer Road Rose Bay.

The only shell that exploded was the one that fell outside Yallambee Flats. It demolished part of a house. A woman sleeping on an enclosed verandah was slightly injured by flying glass. About 12 women lived in the flats. The warning sirens eventually sounded about 10 minutes after the last shell had been fired.

USS Chicago off the Mare Island Navy Yard after her last overhaul, 20 December 1942